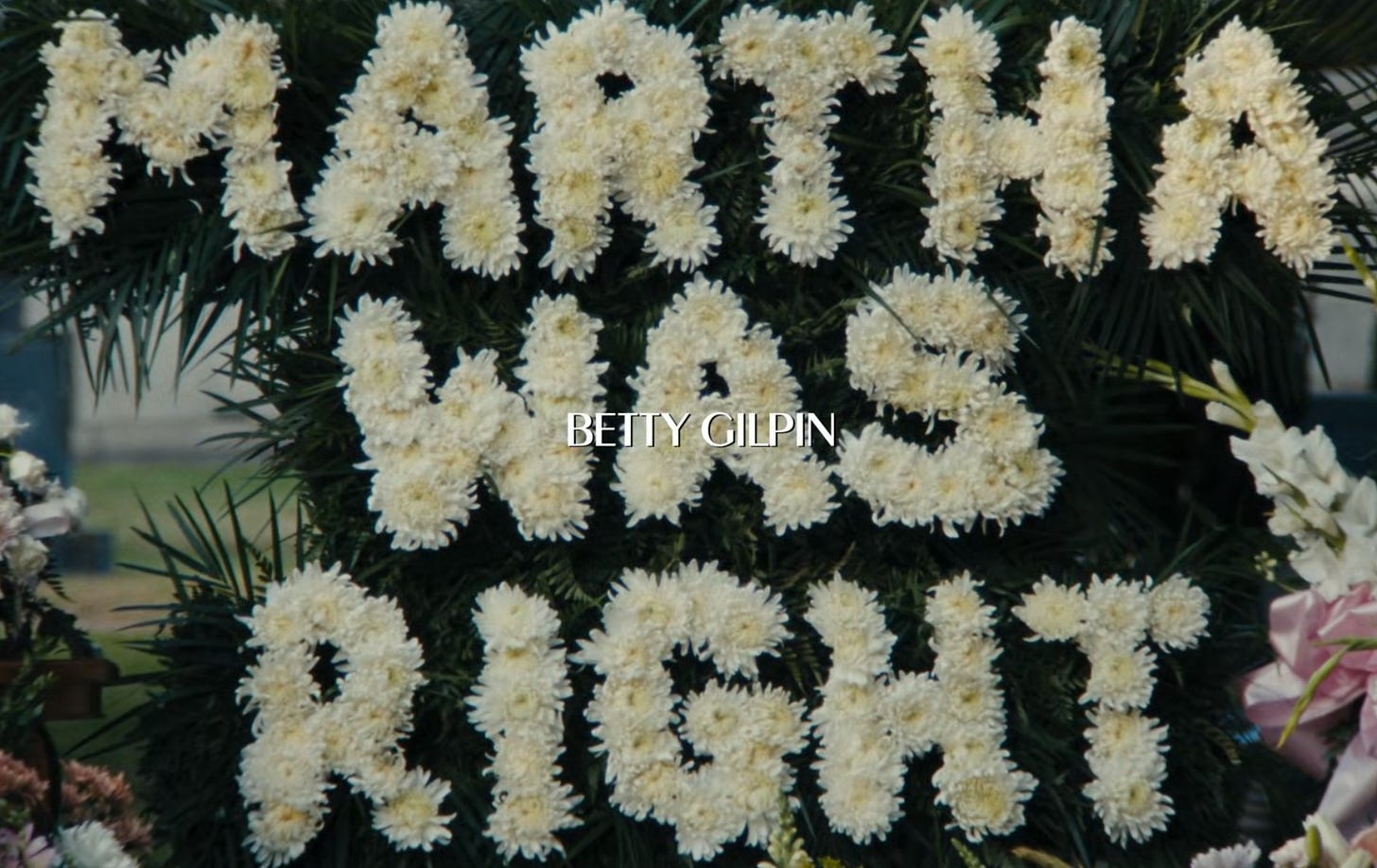

“Martha was right,” spelt out in a large floral arrangement fills the screen in the last several seconds of ‘Gaslit’, an 8-part series from Starz that offers a view of the Watergate scandal that’s less about Nixon than about the machinery that made and sustained him. The Martha who was right was the wife of John Mitchell, Nixon’s Attorney General and the Chairman of his campaign for re-election and one of the main accused in the Watergate break-in. Martha Mitchell was among those who saw through Richard Nixon early on, speaking out about his involvement in the illegal wiretapping, going so far as to suggest that he had not only known about it but had authorized it. While Martha Mitchell’s story forms the narrative cord that ties the series together, there are also a number of parallel threads that fill out the complex saga of corruption and jockeying for influence that was the Nixon presidency—or indeed, any seat of power. One of these is John Dean, White House counsel, who testified against the President and helped usher in the articles of impeachment, while another is G Gordon Liddy, who planned the actual break in. Both Dean and Liddy had successful post-Watergate careers in media, but another minor character in the drama, Frank Wills, the security guard who foiled the break in had his life upended as a result of the “notoriety” gained from all the publicity—and he chose to leave DC for anonymity and quiet in his Georgia hometown.

Most of us in journalism and media studies/practice today can perhaps point to a few instances that stand out as points of intellectual/professional inspiration—big investigative stories, dogged war or crisis reporting, uncovering corruption and social issues. For me, as a rising eighth grader in the early seventies, the Watergate story was what first sparked my interest in journalism. And honestly, it was the story about the story: the book, All the President’s Men, and its 1976 Hollywood version starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. Missing in the television series Gaslit are the two people whose names are perhaps most associated with Watergate, apart from Nixon—Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, played by Redford and Hoffman respectively. The journalistic legend that has been built around the investigation that brought down a president is no doubt based in truth, but what ultimately made the case for impeachment was meticulous police and legal work, and that to some extent is reflected in Gaslit

.

It’s fifty years since the Watergate break-in, and next year is the anniversary of the journalistic scoop, so it’s no surprise that this series dropped when it did. The Washington Post has spent a fair amount of time and newsprint on Watergate nostalgia too, with retrospectives and retellings. Their daily news podcast, Post Reports featured a conversation with Bob Woodward in which he spoke about how the movie came to be (including the persistence of Robert Redford), and the slippages between the gritty and time consuming work that the actual investigation involved (painfully detailed in the book) and the dramatization for the film version.

Anniversaries are, in the cynic’s view, opportunities to monetize memory. But they are also occasions to train a critical eye on the past, to excavate from it the nuggets that yield insight and learning, and possibly draw from it some purpose and inspiration. Journalism today is beleaguered by political and business control, and few publications allow the kind of painstaking, months-long investigations that can bring down presidents. And even when they do, it is the rare judicial and legislative system that will take the results of journalism and use it to clean up the mess that was uncovered.

As a journalism teacher, I find it hard these days to spark in students a sense of this possibility that solid reportage and well researched stories can be powerful tools, that they can speak truth to power. But it’s not impossible to find that kind of journalism—incremental, dogged, characterized by a willingness to spend hours in dusty archives or burrowing through the wormholes of the internet—if one looks closely. In India and elsewhere. But the risks have multiplied, and for those who do this kind of journalism, especially if their target is political or business power, hard work may not be a deterrent but threat to life and liberty certainly is.

Fifty years on, the Watergate story is both inspiring and sobering, for these reasons. It shows what is possible when the watchdog is watching a system that has strong corrective mechanisms. And it reminds us how quickly those corrective mechanisms are being eroded, even in the largest of self-proclaimed democracies.

Postscript: Gaslit is based on a 2017 podcast from Slate, Slow Burn produced and narrated by Leon Nayfakh, which is most definitely worth a listen if you haven’t already.