Sometimes, all you need is a well told story to perceive, with sudden clarity, a whole landscape of interconnected streams that run through the past and ripple under the present, showing us how today’s violence radiates from trauma in the past, how injustices of our times emanate from troubled histories of conquest and dominance.

A few days ago, I received an email from the organizers of a conference I was to attend in Toronto, with a short paragraph to be read out at the start of every session. It has become customary in some countries, such as Australia and Canada and parts of the United States, to formally recognize the relationship of indigenous peoples over un-ceded territories, a tacit apology for the injustices of settler colonialism. While such symbolic statements are no doubt necessary, they also underscore the fact that nothing, really, can make up for those injustices. Reparations, when made, are always too little, too late.

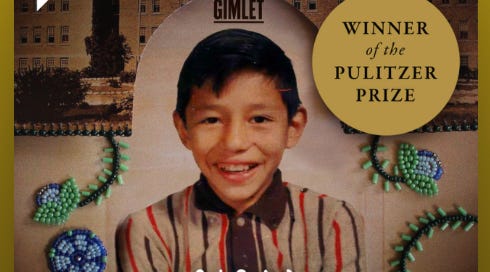

Just a few days before this email I had binge-listened to the second season of the podcast series Stolen, reported and narrated Connie Walker and produced by Gimlet Media for Spotify. The series, titled “Surviving St Michael’s” received a double honour this year—a Peabody and a Pulitzer. It’s not an easy listen, but well worth the time taken to finish the eight episodes, and it will leave you wondering, sad, and with a faint ray of hope that some sort of healing is possible.

It’s a theme that made the headlines in Canada and traveled through much of the world and forced and apology from Justin Trudeau and the Vatican—the atrocity that was the Residential School system for First Nations people of Canada. St Michael’s was one of those, and Walker tells the story of the horrific sexual and physical abuse that hundreds of children, taken from their families, suffered there. The story is personal; Walker’s father was one of those, and the trauma of his early years left a burning rage that burned through many years of his life, affecting those around him. Walker’s story begins with wanting to know what happened to her father at St Michael’s but it’s a story of the entire Cree community of Saskatchewan, with every single family seared by the experience of alienation and abuse.

In Episode 4, survivors share their memories. The voices are old now, but you can still hear the frightened child inside. Some were just 6 or 7 when they were taken from their homes, forced to speak in a new language, in the effort to “assimilate” them into Canadian society.

“We had numbers, we were not known by our names...my number was 654...”

“They made us ashamed of who we were...who we are.”

“My mother had made long braids, and when we went to St Michael’s they cut them all off....”

“...the trauma is etched in your brain.”

And the trauma, once etched in the brain, becomes a poison seeping through family interactions, across generations.

“All the growing up years that were taken away from me...”

“Sometimes we cry for each other...who has been held accountable for the things they have done to us?”

Connie Walker’s investigation exposed more than 200 allegations of child sexual abuse against 16 members of St Michael’s staff. While some of the survivors went through the additionally traumatic process of filing claims for compensation, several just could not face having to dredge up painful memories in a process that placed the burden of proof on the victims of abuse.

So where does the hope come from?

In Episode 3, “Don’t play with this,” Walker speaks with a survivor who has found a way to heal by reclaiming indigenous language and knowledge. The healing, he says, must come from a return to the old traditions, from the wisdom of the Cree, cautioning her against turning it into a vengeful crusade. “We gotta help fix this with indigenous language, indigenous thinking... we don’t profiteer from this...we’ve been to hell and back...but we’re back.”

Stolen: Surviving St Michael’s represents the kind of journalism that podcasting makes particularly effective—intensely personal but no less rigorous. Walker spends as much time in the archives hunting through newspaper clippings and microfilm as she does speaking to scores of elders who attended St Michael’s in the 1950s and 1960s. She reflects, each step of the way, on the ethics of storytelling, of appropriating the voices and stories she has heard, but in the end, you understand that it is her story too.

...

With the request to voice the formal acknowledgment of indigenous people’s relationship with the land on which that conference was being held was the gentle exhortation to not simply pay lip service but to try to feel, to understand, and to speak it with sincerity. Listening to stories like Surviving St Michael’s can to some extent lead us into such feeling, such understanding.

For more information on the residential school system, here’s a start:

So touching. Is it OK Usha if I translate excerpts of this post to Hindi and publish in my newsletter Parikrama (with due credits to you of course)?